The death of the arcade is greatly exaggerated. In Japan, the arcade is actually stronger than ever. Perhaps the most unchanging piece of youth culture and interest is the persistence of the arcade. While I’ve explored perhaps the flip side of these fun machines during the examination of pachinko, today I am looking at a single machine that is omnipresent in public spaces across Japanese cityscapes.

I’m talking of the claw machine. The crane game. Yes, the skilled arcade game that promises plushies at every turn. This is an examination of the great claw.

Claw Causes

Like many other Japanese icons, these machines were not actually invented in the country. Surprisingly, it is a relic of Great Depression USA—not a machine you’d expect would be invented when millions were in mass unemployment. However, that discounts the first rule of gambling and gambling-adjacent activities… you’re never too poor to gamble! (This is not financial advice). For many living through this aforementioned Depression, the chance to have any win felt like a relief.

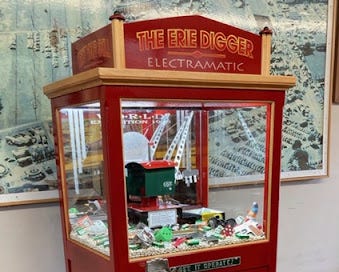

The actual design of the machines haven’t changed much in appearance, either. The concept was based on the giant machines that they used to construct the Panama Canal and other canal-building activities. In fact, the first patented claw machine Erie Digger was named after the Erie Canal, which doesn’t have the same ring to it.

These remained a fixture in American fair and festival life, becoming a country town glimpse into the big city. They became a central figure touring with carnivals as another easy income generator. Realistically, the mechanical machine would be the least ethically compromised attractions among the rest of the less-than-regulated rides, cheery carnies, and well-treated animals.

SEGA steps in

Japan was having none of this excitement for a while, but suddenly, SEGA.

Spotting the value of a giant cash-printing machine, Japanese companies started developing their own claw machines as early as the 1960s.

They were a somewhat popular item then, as they remain now, outside of Japan. Profitable, but also semi-forgotten pieces, sitting in corners of shopping malls, collecting dust as the plushies look outside in that eternal stare. Their depiction in the Toy Story mega-franchise is pretty accurate.

Except in Japan, where SEGA revolutionised it all in 1985; at the height of SEGA’s powers, the first UFO Catcher was born. It was two-player, bright pink and changed everything.

But what did that actually change?

For a long time, their existing crane games weren’t anything different to the rest of the cabinets out there. But after recruiting a new top engineer, Mr Mitsuharu Fukasawa, under false pretences (He joined expecting to work on an actual video arcade RPG that he had already conceptualised and designed), SEGA set him in charge of their failing crane division. In a scene out of every alien/spy/secret plan movie, he was given the resources for a secret team that had one goal. To make the best UFO catcher in the world.

Fukasawa had a deadline of 9 months to revitalise this division. So he got to work. While the most obvious changes were the cosmetic touch-ups, what truly mattered was what was inside. A helpful moral that should be taught in more nursery tales. The biggest issue everyone had with these arcade games were that they just broke a lot. This sucked for everyone involved. The players would feel tricked, the company would lose recurring plays, and the toys inside would never be salvaged. Fairness was the first fix.

Then, it was an advertising spree. The idea was to make the crane game more visible to everyone, so they bumped up the height so that the prizes were now eye level. Potential players could now easily see the prizes on display (now actual SEGA licensed toys). For an outsider, you looked from plushy to man, and from man to plushy, and from plushy to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.

Other quality of life improvements were included, such making it two-player and cementing its status as a classic Japanese drama location. The units also lost their infamous sharp edges which had made them a safety hazard in many arcades, and removed entirely from many non-funhouse horror locations. All in all, the new UFO game was a Catch.

Crane Crimes

Soon, the UFOs had taken over Japan. Now in almost every suburbia shopping mall, it is unimaginable to not find a set of plushies, candy, or even high-end electronics available to be plucked from the sky.

In Japan, these games have become a rite of passage across generations. Young parents teaching their children about challenges, first dates trying to impress via the skill of the claw, rather than skill of conversations, and teenagers spending hours perfecting the perfect drops. As the games have become more central to life, the critics voices have gotten louder.

The first claim is that the game encourages, or is even tantamount to gambling. The game makers push back vehemently on this slander. Despite the UFO machines being a clear example of a game of chance, Japanese society as a whole refuses to acknowledge that this equates to gambling. It falls into the pachinko paradox (see linked article from earlier this piece), where the prize is not of monetary value, and thus not an act of gambling. But how do we know it is a game of chance?

There are publicly available algorithms on the likelihood that a prize is won. This is despite the input of any player’s “skill”. In spite of the overwhelming evidence the claw strength is actually variable, and that the operators can literally program the payout regularity, the randomness remains the key to people’s enjoyment. This element of chance is played coyly by the crane game makers, since they can’t advocate that the games are purely luck and drive away the feeling of accomplishment, but if they remove the luck aspect, it is even more detrimental.

After all, if you were able to maximise on skill, it should mean that every play would result in a prize. Given the intensity of how guests spend their time at arcades, this would turn the whole place into an overly complicated and unprofitable vending machine.

Yet the founding fathers had something to say on that point.

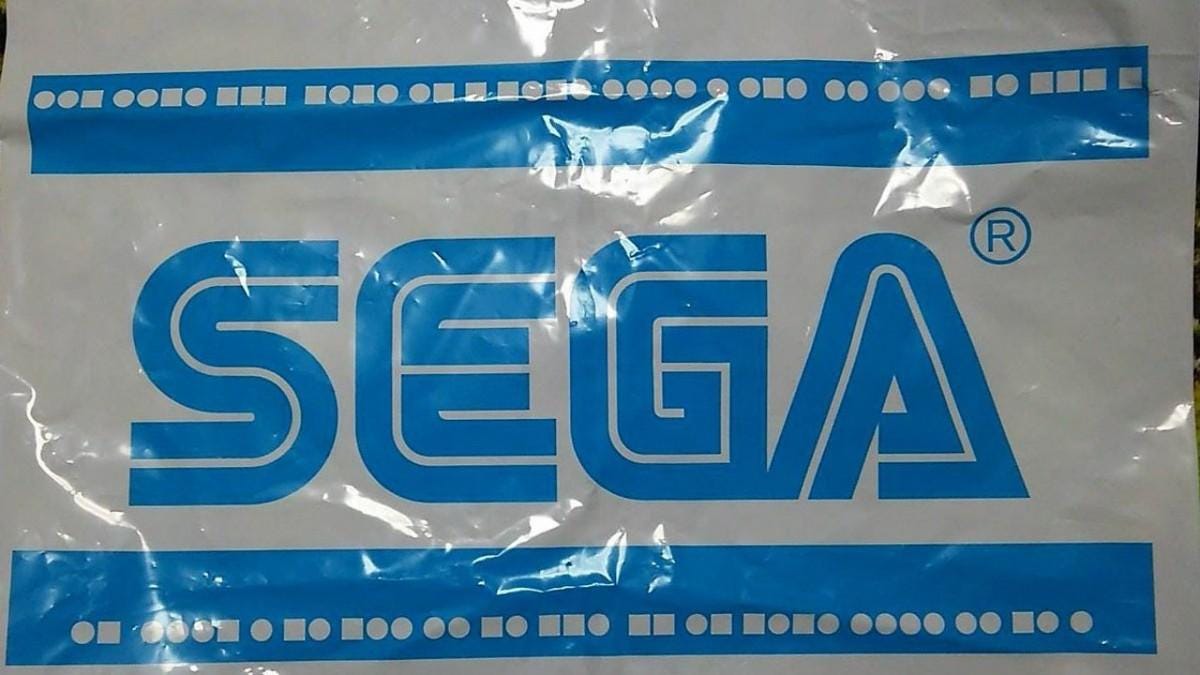

On every SEGA prize, there is the world famous logo as below.

For years, in this very image under every winners’ nose was an alien language with a hidden message to take home. Only in 2014, did communication succeed. A prize winner noticed in the image above that the dots and squares accompanying the S,E,G,A, could mean something. Using their morsing skills, they translated it via Morse Code to read…

“UFO Catcher Is Not A Vending Machine.”

It was the message that SEGA needed everyone to understand. Upon decryption, the player asked SEGA publicly on Twitter if this was the true meaning of the logo. Confirmation quickly followed, ensconcing the law to be carved into stone.

SEGA’s idea is that these are highly specialised tools. They require attendants that guide players on the ways to coax the machine into doing your bidding. To note, there aren’t attendants at every Aeon town or Ario corner claw, but they do frequent the megacomplexes of Gigo and Taito Stations that are in every downtown.

The attendant’s role is an odd one, but to me quite helpful. They are the Charon guiding us simple humans through the land of machines. They know the ways of the ancient and future texts. Even for semi-frequent visitors to a UFO section of any arcade, there always seems to be new and exciting machines that operate ever so slightly differently to the older, now identified FO machines. Maybe they alone hold the secret keys to the kingdom (and also the literal keys to the machines).

At least, that is what I tell myself when I inevitably leave empty-handed.

What do you tell yourself if or when you are foolhardy enough to test your mettle against these metal machines? Let me know in the comments below.

Whatever the type, one should avoid those machines like the plague because they are nothing but coin suckers. Though deceptively easy, your chances to get one of those cute stuffed toys (unless you are blessed with beginner’s luck) are close to naught. It’s not by chance that revenues from UFO Catchers can be as much as 40 percent of all game revenues at arcades in Japan.

The post topic I've been most eagerly awaiting!! Thank you Leon! 🙏