Happy New Year to all adherents to the Gregorian Calendar! If you might indulge me, I’d like to open this post by addressing a few things that have been relevant to Hidden Japan of late.

Mini-update on Hidden Japan

Firstly, I want to thank all my subscribers for reading my work and sharing to friends, family, and acquaintances! Hidden Japan recently tipped over the 1000 subscriber mark, which has exceeded my wildest expectations when I started writing a little over half a year ago.

I also want to note the recent lack of activity. While I’m sure the only item on your holiday wish list was more Hidden Japan, I want to apologise to everyone as I’ve been particularly offline this period due to a family medical emergency. Thank you in advance for all the well-wishers, luckily the crisis appears to now be more settled and resolved into a slightly stressful memory. If my absence was not noticed, hopefully this post and the planned posts for this year will leave you waiting with bated breath for more Hidden Japan. I will be back to a weekly free post schedule, as well as the regular paid posts for premium subscribers.

Now onto the actual Japanese content! And what better way to celebrate both Hidden Japan reaching the 1000 subscriber mark and the still-recent advent of the New Year, by discussing fireworks.

We didn’t start the flower fire

Fireworks feel both oddly historical and extremely modern at the same time. Growing up in Sydney, the annual New Year’s Eve fireworks were really an excuse for people to gather and complain “that no new innovations have occurred with the fireworks this year”, or “I can’t believe we’re wasting this sort of money on it”. As though exploding safe, colourful and explosive flames, hundreds of metres in the air that can be seen across a city isn’t impressive enough.

So how did people come to associate fireworks with celebrations, and the regret of another year gone by? I’ll start with a brief history. Like many historical inventions including paper, the abacus, and the dual-purpose motorbike toilet, fireworks originated in China in about 200 AD (or the Song Dynasty). Fireworks followed from the controversial invention of gunpowder, and were quickly adopted as means of celebration. From this starting point of reactive loud crackles, much of the development became interlinked with warfare. While gunpowder is now closely linked with a specific weapon (guns), China focused on the role it could be used as long distance communication, with military coloured smokes and signals. Leftover inventory slowly became adopted in the civilian world, and fireworks became linked to certain festivals that warded off demons, evil spirits, annoying people and the like.

About a thousand years on, roughly in 1600, Japan hears the loud bangs on their soil for the first time. This wasn’t introduced by the neighbours, but by the insistent Europeans who kept wanting to trade. The arrival of fireworks were an instant success, and Japan chose to celebrate this by lighting fireworks in response. The divergence of firework innovation can be seen in the language used; Even today in traditional Chinese (烟花), the literal translation is smoke flowers, whereas Japan seemed to focus on the actual lit up fire part and now know them as Hanabi (花火) or flower fire.

Controlled burning

The move for Japan to host fireworks as a more central part of Japanese culture was pretty circumstantial.

The steps needed were:

Know how to make fireworks

Have access to gunpowder

Don’t use up your limited supply of gunpowder for violence

Have a place that demanded new and exciting cultural events

17th Century Edo Period Japan finally had these in place, with a period of unification (internal peace) and a big new capital city (Edo) where people wanted things to do. With an excess supply of gunpowder and no wars in which to use them, new people in the city started experimenting. Presumably this was done safely, but there were regular recorded warnings for expulsion from Edo from the government about not causing fires.

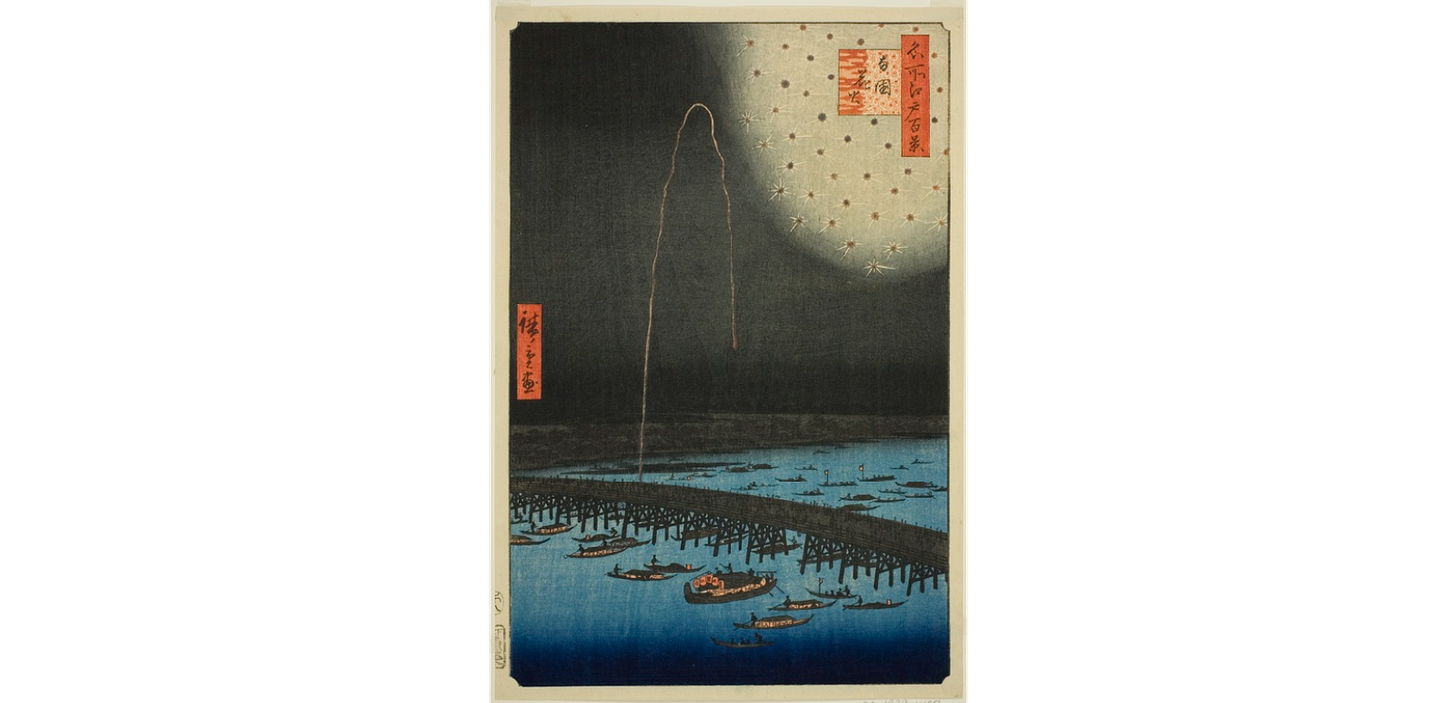

It was in 1733 that the big shift in Japanese public sentiment changed. It went from “wow these are cool, but also they might burn everything I know and love”, to “this display is culturally and religiously significant, and I want as many as possible”. This was the year of the Sumida river display.

If that doesn’t ring a bell, this became the first government sanctioned lighting of fireworks, designed to memorialise victims of famine and cholera. The city employed famous firework fire-workers from across the country, as well as enhancing the longstanding family artisans that still exist, now multiple generations away from the Edo Period. With long-time pyro enthusiasts commissioned, this marked the first Shogun sanctioned firework viewing party. From this point, Edo decided that fireworks were going to be their thing, as a public spectacle and to distinguish it from the commercial hub of Osaka and the cultural centre of Kyoto. These days, at the same Sumida River, the annual Sumidagawa Hanabi Taikai occurs more to keep up tradition and (slightly) less to do with cholera.

Catching Fire

With the officials onboard, fireworks burst into Japanese public life and have kept rising in popularity. The firework frenzy spread from just Edo to across the country, as designs became more interesting than just coloured smoke. Like any good gang battle, competitions between rival families drove designs forward, including much more modern-looking designs like the chrysanthemum and peony firework. Despite being invented almost 300 years ago, these are still foundational shapes that anchor any good celebration. You’ll know them when you see them.

Nowadays, these public spectacles are really found wherever you go in Japan. It would be physically impossible to actually attend all of them in a given year with the current number of festivals at around 8,500 annually, or a little over 23 an evening.

Yet, unlike the West, the big displays aren’t centred on the New Year. Sure, there are some festivals to appease the faithful, but the banging really starts in summer, probably as winter is reserved for illumination.

So where to go for the best pyro?

For me, I’m satisfied with an uncrowded view with some bright lights. If you’re after a consistently good option, almost all coastal cities and towns tend to hold regular fireworks weekly or even more frequently over the summer period. Of course, for the big stuff, you go where the competition is. Yes, even to this day, designers will challenge each other over who makes the best and brightest boom. The winner is inevitably the public or at least the public who don’t mind crowds, as 600,000 attendees visit the annual August Omagari Fireworks Competition in Daisen City.

To me, the joy of fireworks is the ephemeral nature of it. Even if there are 8,500 chances to see them every year in Japan, each display will naturally be unique with changes in people, atmosphere and time. It makes sense why people use it to mark a year in their lives, as life itself can be as fleeting as the fire flower. Also, fireworks are nice and pretty!

Congrats on 1000 and I'm glad your family emergency seems less emergency-y. Looking forward to your posts in 2024!

Nice! Glad your crisis has been, for the time being, weathered.

The fireworks I'm looking forward to are also, I believe, in Ryogoku; at the Kokugikan, where the January Sumo Basho will start in a week or so.

Always helps get me through the dreary Ohio winters.